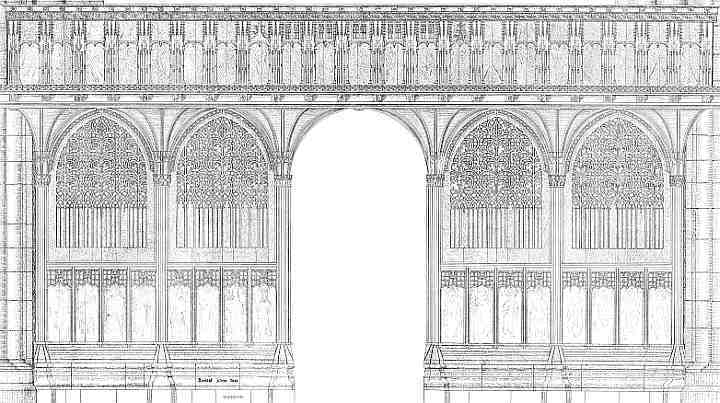

For nearly 500 years a massive wooden screen has cut off the chancel from the crossing, transepts and nave of St Andrew's Church. A broad platform or loft juts out over its ribbed and painted arches. Since 1819 the loft has been occupied by four successive organs, the last installed in 1974.

Perhaps the loft was once the setting for the Rood: an awe-inspiring carved Crucifixion, richly colourful and dramatically lit, with life-size (or larger) figures of a sorrowing mother and disciple at the foot of the Cross. Below, on parapet and screen, rows of painted or sculptured saints each bore the symbols of his own sanctity. The whole coloured and gilded spectacle, aglow with the light of many candles, focused the attention of worshippers on Christ's sacrifice for Mankind. Once, every church had such a rood, set upon a rood-beam or rood-loft above the screen that separated chancel from nave. Usually the screen was an open one, with wide gaps between slender uprights that allowed the congregation to watch and share in the priest's celebration of divine worship; stone newel stairs cut into the wall nearby ascended to the loft so that candles might be set around the rood. Only in some greater churches, and particularly those served by monks or canons, was there a more solid and substantial screen; double fronted and stone-built.

The screen at Hexham is in fact a Pulpitum, meant to close off the canons during their worship in the quire. Unusually, the Hexham pulpitum is of wood, but it made a compact enclosure which the canons entered through a central passage. There, they were shielded from lay parishioners and from some of the draughts. Whether in fact our pulpitum also served as a Rood Screen cannot be certain and perhaps it is simplest to know it by the name of the Prior who had it built, Thomas Smithson.

Thomas Smithson, who headed the Priory from 1499 to 1524, claims responsibility upon the screen. You can read his message on the bressummer, the long beam that stretches from pier to pier above the vaulted arches at the base of the loft parapet In the row of small squares or pateræ along that beam appear Prior Thomas's words, contorted and crammed into their own initials:

Orate Pro Anima Domini Thomæ SPriori Huius Ecclesia Qui Fecit Hoc Opus

(Pray For the Soul of Master Thomas S[mithson] Prior of This Church Who Made This Work)

Below, the painted saints remain, though darkened with age, battered and restored. So far as they can be identified, they seem to be bishops of Hexham or Lindisfarne, including Cuthbert bearing the head of St Oswald; but the names and regnal periods added later are often illegible aid probably misleading. In the vaulting above, the rich colour and gliding that once glowed in the light of many candles is similarly faded with age. Only when the screen is fully and harshly lit is some vestige of its original splendour apparent.

As the canons processed between the saints and into the quire, they passed on each side doors opening into the screen enclosure; inside that dark space spiral stairs of stone (on the south) or wood (north side) led up to the loft. Above the doorways, though now scarcely seen without their individual lights, are two of the finest paintings in the whole church. On the north side the Annunciation shows the archangel Gabriel bringing his message (conveyed in a now illegible scroll to the Virgin, as reported in the first chapter of Luke; a symbolic potted red lily grows between them. The sequel, the Visitation of Mary to Elizabeth, who was soon to give birth to John the Baptist, appears on the south side. The two expectant mothers congratulate one another outside a Jerusalem that looks as though it may be modeled on Hexham's Moot Hall.

We do not know whether Prior Smithson's pulpitum also served as a rood-screen. Almost certainly part of an earlier rood-screen of stone remains, against the south wall of the nave. The moulded jamb of an arch suggests the entry on each side usual in the rood-screen of a monastic building. This screen, built long before Smithson's, may have continued to function at the same time; or perhaps the new screen replaced it as the nave passed out of use.

Smithson's screen was one of the last additions to their church made by the canons. Thirteen years after his death the Priory was dissolved by royal command. The buildings passed to Henry VIII's loyal supporter, Reynold Carnaby, who made his home in the former living quarters but allowed the townspeople to continue using St Andrew's as their parish church. With no canons, the screen that had shielded their secluded worship was no longer needed, while the Protestant and puritanical Reformers who reshaped Anglican worship over the following century scorned its Popish imagery. Yet somehow the screen survived, and even kept some of its array of saints.

Two notable features of the screen are gone. If the Rood itself ever existed, the image of Mary and John sorrowing at the foot of the Cross was soon discarded; roods and rood-lofts were finally banned in 1561. The gilded statuettes that occupied the line of niches below have also vanished without trace, save for some of the canopies that protected them. But the panels below, with their richly convoluted tracery, long remained to close the arches and shut off quire from crossing. When in 1908 the new nave was built and the quire reorganized, the panels were provided with hinges so that they might be thrown open during services; at the same time the internal stairways, which had once served for gospeller, epistoler and organist to climb to the loft and deliver their messages, were removed, and replaced by a cast-iron spiral stair beside the screen.

On the eastern side of the screen there was some widening of the loft about 1866, making a projecting balcony to accommodate a new organ, and the saints pictured there were rearranged. They include St John the Evangelist, St Oswald, St Etheldreda, and St Andrew. Like all the paintings on the screen, they presumably date from the first quarter of the 16th century, and were still fresh and bright when the life of the Priory ended. With many other Abbey paintings, they were restored to something of their former brilliance during and after the 1950s.

Prior Smithson's screen served as a Pulpitum and perhaps also as a Rood Screen. Whatever its purpose, we are fortunate that such an impressive structure survives from the last troubled days of the Priory.